Project Risk Management — An 8-Step Process to Success

The latest project management statistics show that a significant 34% of project managers don’t implement risk management into their projects.

Considering that project risk management exists with one purpose — to maximize the chances of project success — these numbers must change for the better.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through an 8-step process that will help you implement risk management practices into your projects. After that, we’ll provide you with valuable expert tips on how to manage and reduce those risks.

But, before we can talk about managing risks, we first have to establish what exactly risk management is in project management.

- Project risk management is the process of identifying, analyzing, responding to, and monitoring project risks.

- Project managers should engage in risk management both before and during the project.

- Project risk management should consider both positive and negative risks.

- Having a strong risk management plan helps prevent negative risks, deal with issues, and take advantage of positive risks.

- Strategies for dealing with threats include avoiding, escalating, transferring, mitigating, and accepting the risks.

- Strategies for dealing with opportunities include exploiting, escalating, enhancing, sharing, and accepting the risks.

Table of Contents

What is risk management?

According to The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects by PMI, risk management is the process that shapes decision-making across the organization and involves 4 major steps:

- Identifying,

- Analyzing,

- Responding to, and

- Monitoring risks.

To avoid ambiguity, the term project risk refers to both opportunities and threats. Opportunities are positive risks, whereas threats are negative risks. On top of this, a negative risk that occurred is referred to as an issue.

Project risk management is an important process as it helps:

- Anticipate and manage change,

- Improve decision-making,

- Implement lower-cost preventive actions instead of higher-cost reactions to issues,

- Increase the chances to realize opportunities,

- Raise awareness of uncertainty of outcomes,

- Support resilience, and more.

Instead of simply predicting possible outcomes, project risk management aims to develop the means to achieve project objectives.

Our collaborator, Tres Roeder, the founder of Roeder Consulting, and a PMP, PMI-ACP certified author of A Sixth Sense for Project Management and Managing Project Stakeholders, claims that risk management should be performed both before starting a project and throughout the project:

“At the early stages, risk management will help the team identify and understand the variable forces that will impact the project. It’s more important to understand the project’s sensitivity to each of these risks than it is to perfectly predict the exact timing or magnitude of the risk. If the risk could be predicted, after all, then it would not be a risk at all and would simply be added to the project plan. During project execution, it is important to re-evaluate the risk picture on a regular and ongoing basis. Things change.”

📖 Now that you what risk management is, you can dive further into the topic of project management — check out our Project Management Glossary of Terms and get acquainted with project management terminology.

What are the steps in a risk management process?

The risk management process will help you successfully manage risks in any type of project by following these 8 steps:

- Identify risks,

- Assign risk owners,

- Perform qualitative analysis,

- Perform quantitative analysis,

- Prioritize risks,

- Plan risk responses,

- Implement risk responses, and

- Monitor risks.

Let’s dive deeper into each step.

Step #1: Identify risks

The first step in any project risk management plan is always to identify the risks.

Usually, you start by brainstorming possible risks. This process should include:

- Your project team,

- Stakeholders, and

- Outside experts.

After that, you should enter all the identified risks into a risk register — a document used for tracking all potential risks for an ongoing project.

Many companies also run so-called risk repositories — compendiums of all the risks identified across all projects carried out by the company.

Keeping a risk repository helps out with risk identification as you’ll already know what to expect going into new but familiar projects.

While identifying risks, you should also know the difference between risks and risk impacts.

To give an example, let’s say your project objective is to create and maintain a social network.

This entails dealing with confidential information.

Potential leakage of said confidential information can cause great damage to the company and brand.

But this PR nightmare isn’t the risk — it’s the impact the risk will have if it occurs.

In this case, the risk is the leakage of confidential information.

A risk response to this may be the implementation of tighter procedures and safety measures to prevent the risk from happening.

Risk response plans have to take the risk into account to prevent or minimize its impact.

Therefore, whether or not you can identify the risk correctly will directly affect your ability to plan for said risk.

💡 Plaky Pro Tip

Project risks are often confused with project assumptions — read this blog post to learn the difference:

Step #2: Assign risks owners

At the end of the day, the project manager is the one bearing accountability for the project as a whole.

However, more often than not, the project manager is not the one actively monitoring all potential risks.

Instead, what they do is assign risks to different team members to monitor.

In most cases, team members have risks assigned to them based on their project roles and responsibilities.

If shipment delays are a potential risk, the person who maintains contact with the shipping company is assigned to that risk. They will monitor the situation for risk triggers and report any changes to the project manager.

The same goes for the team members who do maintenance or operate equipment — they get assigned to monitor the risk of equipment malfunction.

By assigning risks to team members, project managers can focus on more pressing matters while at the same time keeping a fresh pair of eyes on the status of each risk.

This ensures that the team can assume a more proactive approach towards project completion.

Step #3: Perform qualitative risk analysis

Once the risks are identified, it’s time to analyze them to gain a better understanding of individual risks.

According to The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects, qualitative analysis may be done by evaluating various characteristics, such as:

- The severity of the impact on the objectives,

- Manageability,

- Timing of possible impacts,

- Relationship with other risks,

- Likelihood of risks occurring, etc.

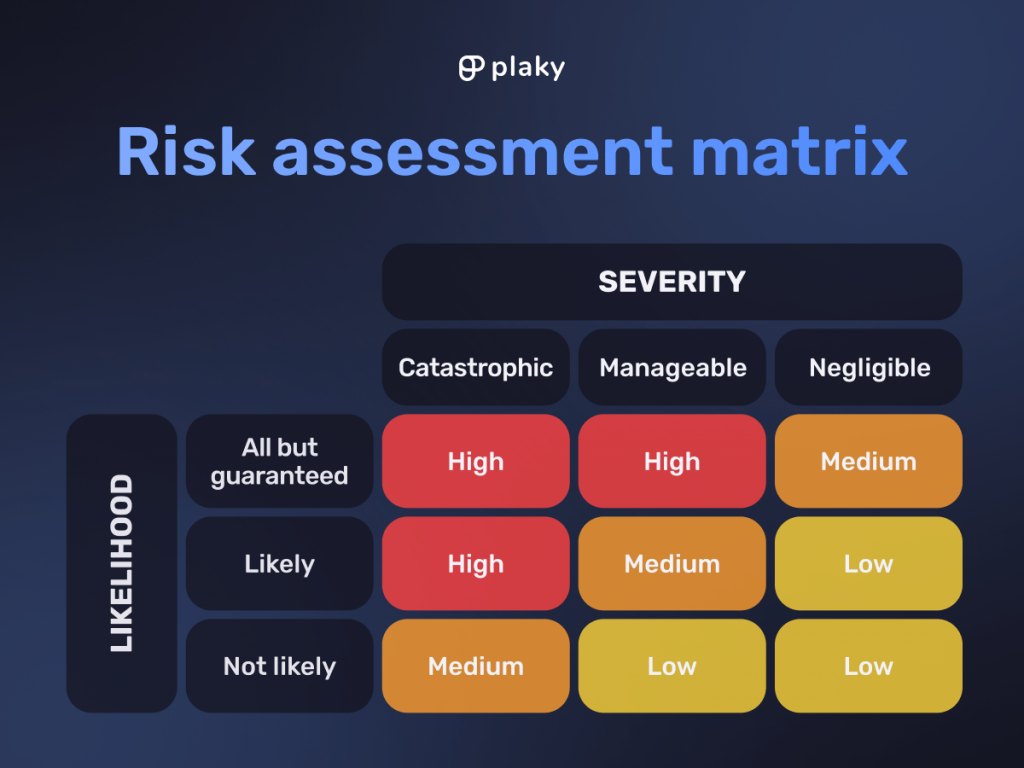

Qualitative analysis is often represented in the form of a table known as the risk assessment matrix.

The table below is an example of a risk assessment matrix evaluating the degree of risk likelihood and severity.

The more potential risks your project suffers from, the more benefit there is in creating a comprehensive risk assessment matrix.

Regardless of the size of the matrix, once you have it, you can determine where each risk slots into.

Step #4: Perform quantitative risk analysis

While qualitative analysis mostly relies on guesswork, quantitative analysis takes a much more scientific approach to risk analysis.

Quantitative analysis uses empirical data to arrive at accurate predictions related to the severity of the impact of certain risks.

The biggest advantage of quantitative risk analysis is that you can get tangible, numerical answers to questions such as how much a certain risk will affect:

- Project budget,

- Project timeline,

- Project scope, or

- Project resources.

The downsides to quantitative analysis are the following:

- It requires extensive data collection, and

- It is complex.

Before you can do your thorough analysis of data on a project, you first need to acquire the data.

This is easily done when your current project shares a lot of similarities with previous projects.

After all, the relevant data is contained in old documentation and the risk repository.

But if you’re embarking on a project that is unlike anything the company has ever done before, then you won’t have enough data to do proper quantitative analysis.

In addition, quantitative data analysis is complex to the point where it often demands the use of specific software to compute.

The concept of diminishing returns is integral to understanding why many project managers still opt for qualitative analysis — if something requires twice the effort but only yields a 10% improvement, then it’s simply not worth the effort in most cases.

Deciding which type of analysis to use is often done on a risk-by-risk basis.

Sometimes, the extra effort is worth it, but not always.

Step #5: Prioritize risks

It’s not uncommon for a project to come under fire from several risks at once — so knowing which risks to prioritize can be a great asset.

When prioritizing, you should keep in mind the following concepts:

- Risk appetite — it refers to the amount of risk an organization is willing to expose itself to in pursuit of its goals. An organization that is unwilling to take any risks is unable to grow, whereas one that takes any and all risks with reckless abandon is doomed to fail.

- Risk tolerance — refers to the level above which you refuse to expose yourself to any further risk. You can think of risk tolerance as the uppermost limit of your risk appetite.

- Risk threshold — refers to the level of risk exposure that spurs the organization into action. Risks below the threshold are, in most cases, simply accepted. When a risk crosses the threshold, it must be addressed.

Being aware of these 3 concepts should provide you with enough information to better prioritize risks and strengthen your risk management plan.

Step #6: Plan risk responses

Regardless of whether you use qualitative or quantitative analysis to determine the threat level of risks and prioritize them, you need to create a response plan to account for each risk.

The level of detail you want to go into with the plan depends on the risks and projects in question.

For example, it’s taken for granted that unwanted bugs will constitute a risk that is both highly likely to occur and bears great severity on the overall quality of software-related products.

One risk response plan for dealing with bugs might be to tighten quality assurance (QA) and introduce new procedures — whereas another might be to expand the QA team.

Another potential risk might be uncertainty surrounding vendors and their ability to procure parts, materials, and other resources needed for project completion.

Any delay, shortage, or price inflation on their end can influence the budget, timeline, scope, and/or quality of the project.

In this case, the risk response plan may include:

- Additional budget allocation,

- Redundancy,

- Guarantee or punishment clauses in the contract with the vendor, or

- Having different vendors on standby.

It’s also helpful to determine what constitutes the risk trigger for each risk.

Risk triggers are indicators that potential risks have either turned into issues or are about to.

Risks that score higher on the risk assessment matrix naturally warrant more detailed response plans — but this ultimately comes down to the project manager in charge.

Step #7: Implement risk responses

The main point of having a risk management plan is to allow the team to assume a proactive approach towards:

- Preventing negative risks,

- Dealing with issues that could not be prevented, and

- Capitalizing on positive risks.

According to the PMBOK Guide (7th Edition), there are 5 risk management strategies to respond both to negative and positive risks.

Negative risk response strategies include:

- Avoid,

- Escalate,

- Transfer,

- Mitigate, or

- Accept.

Positive risk response strategies include:

- Exploit,

- Escalate,

- Enhance,

- Share, and

- Accept.

We’ll further deal with each of the strategies in a separate section.

Step #8: Monitor risks

Monitoring risks is an ongoing process that spans the entire project timeline.

It allows the project management team to:

- Reevaluate the status of the previously identified risks,

- Identify any secondary risks, and

- Determine the need for reassessment.

At the end of the project, the periodic audit findings should help identify lessons learned for all future projects regarding, e.g.:

- Appropriate levels of resources,

- Time needed for the analysis,

- Use of tools,

- Level of detail, etc.

💡 Plaky Pro Tip

If you like working in Excel, you can check out our Excel risk management template in the post below and tailor it to your liking:

What are negative risk management strategies?

Now, let’s dive deeper into the 5 possible responses to negative risks, i.e. threats.

Strategy #1: Avoid negative risks

Avoiding the risk isn’t as elegant a response plan as it may sound.

In many cases, avoiding the risk means shutting the project down because it exceeds your risk tolerance.

For example, while this information was never publicly disclosed, many speculate that Google Glass — the glasses-shaped android device that used the lens as a display — was discontinued shortly after its release to avoid risk.

Why might this be such a popular theory?

Well, as it turns out, Google Glass proved incredibly contentious about privacy laws and regulations. Even before the product was discontinued, its use had been banned in many places, including theaters, concerts, schools, vehicles, banks, ATMs, and casinos, just to name a few.

In other words, the risk posed by potential legal repercussions was not worth bearing. Having exceeded the company’s risk tolerance, Google elected to avoid any further risks entirely by shutting the project down.

Strategy #2: Escalate negative risks

Escalation is appropriate when the project team agrees that a certain threat is outside the project scope or that the proposed response exceeds the project manager’s authority.

In such cases, threats are escalated to the appropriate level, e.g. to be managed at the enterprise, portfolio, or program level.

Strategy #3: Transfer negative risks

Transferring the risk is a response plan that seeks to mitigate risks that stem from third parties using:

- Contractual obligations,

- Insurances,

- Guarantees, and/or

- Penalties.

For example, shipping delays that can lead to your product not hitting the shelves on its release date constitute a risk that most would rank highly on the risk assessment matrix.

To prevent this, organizations will often impose contractual penalties on shipping companies in case of delays.

Transferring may not be the most appropriate name, as your project will still suffer if things go wrong.

However, the penalties serve as a response plan intended to minimize the chance of threats becoming issues.

Strategy #4: Mitigate negative risks

Risk mitigation strategy refers to taking precautions to minimize the probability of risk occurrence for risks that cannot be transferred.

For example, if workflow bottlenecking caused by equipment malfunction is a risk, one way to mitigate it would be to increase the frequency of equipment maintenance.

The equipment may still malfunction — but you’ve taken precautions to minimize the chance of this happening.

Strategy #5: Accept negative risks

Accepting the risk is a viable strategy. For risks that rank low on the risk assessment matrix, accepting them is sometimes the only response.

It entails doing nothing to minimize the chances of the risk happening.

That being said, we still differentiate between 2 types of risk acceptance:

- Active risk acceptance — i.e. taking actions to minimize the impact of risks, and

- Passive risk acceptance — i.e. taking no actions aside from documentation.

The simplest example of risk acceptance is in relation to natural disasters.

Unless you’ve got the power to control the weather, you can’t hope to prevent a storm or a flood.

Nevertheless, you can still prepare to minimize the consequences of these or any other events on your project outcomes.

And in the equipment malfunction example, actively accepting the risk may mean having redundant equipment on standby.

What are positive risk management strategies?

Now, let’s further examine 5 possible strategies to respond to positive risks, i.e. opportunities.

Strategy #1: Exploit positive risks

Exploiting the risk means making active efforts to bring the likelihood of the risk occurring as close to 100% as you can.

If the positive risk is a substantial bonus for completing the project early, exploiting the risk may mean diverting other resources into this project to guarantee this happens.

Strategy #2: Escalate positive risks

Similar to the escalation of negative risks, opportunities should be accepted by the relevant party within an organization.

This means that the opportunity should be escalated to the level that matches the objectives that would be affected if the opportunity occurred.

Strategy #3: Enhance positive risks

Enhancing the risk is a less aggressive approach to exploiting it.

You make some efforts to increase the likelihood of the risk occurring — but you don’t pursue it to an exploitative extent.

For example, motivating the team to put in some extra work with a bonus increases your chances of positive risk occurrence, but it’s far from a guarantee.

Strategy #4: Share positive risks

Sharing the risk entails getting a third party in on the action — usually because you are unable to seize the opportunity without them.

A common example includes companies partnering to bid for a project they would otherwise be unable to land on their own.

Strategy #5: Accept positive risks

Accepting the positive risk simply means acknowledging it — but not making any effort to increase its chances of happening.

If it happens, that’s great. If it doesn’t, no harm done.

Tips on how to manage and reduce risks in project management

Now that you know all the theory about project risk management, it’s time to seek advice from experts who have some real-life experience with managing risks.

Let’s see what valuable tips they have to share.

Tip #1: Manage risks from the start of the project

Our collaborator, Jeff Mains, a 5-time entrepreneur and the CEO of Champion Leadership Group LLC, highlights the fact that risk management is essential to the achievement of both project and business goals.

Jeff advises implementing risk management into your project from early on:

“First and foremost, project planning should include risk management. Early risk identification, impact assessment, and mitigation techniques are crucial. This proactive approach manages risks from the start of the project. Project managers should also review the risk management plan during the project. Staying watchful is essential since risks might change.”

Tip #2: Raise risk awareness within the project team

Jeff also highlights the importance of joint team efforts in managing project risks:

“I also emphasize risk-awareness in the project team. Project managers should encourage team members to report risks without repercussions. This collaborative approach helps identify risks early, and fosters risk management responsibility. For project success and corporate resilience, risk management should be an ongoing effort.”

Tip #3: Don’t neglect the positive risks

Tres Roeder reminds us that, to be able to fully understand the whole picture, you shouldn’t neglect the positive risks:

“When project managers think about risk, in most cases, they focus on bad things that can happen to their project. It is important, of course, to be aware of “negative risks” and to develop plans to prevent them from happening in the first place, or to mitigate their impact if and when they do happen. However, this is only part of the risk puzzle. Project managers should also think about good things that can happen to their project. These “positive risks” improve project outcomes if they occur. Positive risks should be identified and planned for too. Only through a comprehensive understanding of both negative and positive risk will the project manager be positioned for success.”

Risk management is paramount to increasing project success rates

Risk management is one of the most important project management hard skills to master. This is because risks are all but a certainty in project management. The projects that effectively account for everything that can go wrong are the ones most likely to succeed.

With this guide in hand, you have all the knowledge needed to create a risk management plan and avoid some common pitfalls.

But, much like a surgeon is unable to perform surgery without the proper equipment, risk management also cannot operate off of knowledge alone.

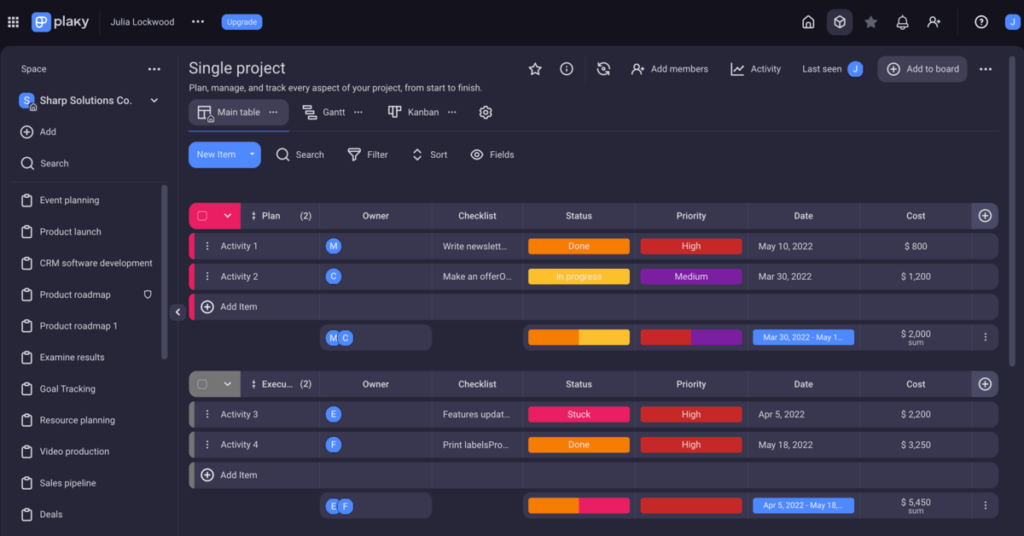

To this end, we highly suggest using a dedicated project management tool like Plaky to easily manage your projects and maintain the project’s risk registry.

When you have all your project information in one place, mitigating risks becomes easy. A comprehensive and intuitive tool like Plaky is sure to improve your risk management strategies. Sign up for Plaky’s free account today.

References

- Bisson, C. (2014). Risks aren’t always negative. PM Network, 28(8), 24–25.

- Cooper, D. F. (2005). Project Risk Management Guidelines: Managing risk in large projects and complex procurements. J. Wiley.

- Hillson, D. (2001). Effective strategies for exploiting opportunities. Paper presented at Project Management Institute Annual Seminars & Symposium, Nashville, TN. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- Hillson, D. (2012). How much risk is too much risk? Understanding risk appetite. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2012—North America, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- Lavanya, N. & Malarvizhi T. (2008). Risk analysis and management: a vital key to effective project management. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2008—Asia Pacific, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- PMI. (2021). The standard for Project Management: A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide).

- Project Management Institute. (2019). The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects.

- Risk register – acoss resilience. (n.d.). https://resilience.acoss.org.au/the-six-steps/managing-your-risks/risk-register

- Shrivastava, N. K. (2012). Project risk management—another success-boosting tool in a PM’s toolkit. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2012—North America, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- Virine, L. (2010). Project risk analysis: how ignoring it will lead to project failures. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2010—North America, Washington, DC. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Project Management Hub

Project Management Hub